When the COVID-19 pandemic changed maternity care, Perth researcher Dr Zoe Bradfield and colleagues surveyed more than 3,000 Australian women about how it affected them. They reveal what women said about the impact of pandemic maternity care on women and babies – both positive and negative.

Do you think there’s been enough research and consideration by health authorities of the psychological impacts of COVID mitigation strategies during pregnancy and birth? In addition, what is the effect on rates of trauma?

It’s a good question. In terms of longer-term impacts, we’ll have to wait and see. However, regarding critical implications, our study looked at data from the first wave of lockdowns after the pandemic in March 2020. It showed people’s acute distress in response to the rapid changes to maternity care – the almost overnight shutdown and redesign of access and provision of care. There was a range of responses.

The types of psychological impact we saw were women talking to us about feeling alone and scared. There was also that real sense of grief and loss. Those were the stories that were hardest to hear. Most of us go into pregnancy and birth with an optimistic outlook, but the changes left parents with a sense of, ‘I don’t know what this will be like for me. I don’t know what will happen when I arrive at the hospital’.

71% of the people we surveyed missed out on antenatal education, either face-to-face or virtual. Antenatal education is the primary source of readiness for birth, particularly for first-time parents. So that sense of being alone, unsure, and the grief and loss that spreads through a space is normally quite anticipatory and hopeful – those are the things we may see the impact for in years to come.

It wasn’t just the pregnant women; it was also their partners. Traditionally, antenatal education involves the woman and their partner. However, partners also did not have access to antenatal education. So, they felt stuck in the middle and responded with powerful feelings of anxiety, psychological distress and isolation. We were completely locked down in the first wave, so our ability to network and even having a conversation around the water cooler was removed.

The reality is we’re still in a pandemic. It hasn’t gone away like we hoped that it might. So how we provide care is still impacted around Australia. Some care is good, some bad.

What are some of the positive changes to maternity care to have come out of the pandemic?

Particularly for families who already had one or more babies, they told us, ‘Having no visitors on the postnatal ward works well for me. It was just me, my partner and my baby.’ And whilst it was distressing not to have younger siblings come in, it created this bubble of 24 to 48 hours of mum, dad and the baby.

Also, the lockdown was positive for some. Not for all – we know not everyone is safe in a lockdown. But some enjoyed not having visitors pouring in and out of their houses.

Also, having their partners locked down at home with them meant they had more practical and tangible support. For others, it increased their stress. But for many, it was a positive experience for them to be together as a tiny family.

We know we have a roughly 40% migration rate in Australia, so the women giving birth to the first generation of Australians have overseas families who couldn’t visit. That’s a powerful story to tell in our multicultural society. There are traditions around this auspicious period of becoming a mother for the first time. For example, many cultures worldwide have a 30-day ‘lying in’ period, where the mum is not expected to do much except eat, sleep and feed the baby. I think all cultures should have that, that’s a fantastic idea! However, overnight, their ability to access it changed.

Do you have any advice for women to ensure they’re still making decisions for themselves? Plus, advice on providing informed consent about labour and birth if they find COVID-positive at the time? Or during a time of tight restrictions for everyone?

The pandemic doesn’t change the fundamental principles of informed consent. They remain the same. Bodily autonomy and self-determination don’t walk out the door because we’re in a pandemic.

It’s vitally important that women go with a clear understanding of what the expectations are in the setting that they plan to birth. They need to understand the practices and the guidelines that advise the area where they are birthing.

We know that many women changed where they planned to give birth. We’ve seen homebirth rates more than double nationally because women wanted to be sure who could be with them, who could support them and for what duration. We have seen women actively vote with their feet by choosing to give birth at home or in settings that are not as restricted.

I encourage women to engage with their care providers to understand the guidelines and principles of care in the setting that they’re in. And to also enter conversations around how that marries and matches their preferences. The reality is that when a woman goes to a hospital, there are guidelines and expectations about how she will care.

But informed consent means that a woman must be fully informed to provide consent for any procedure or recommendation for receiving or not receiving care. Additionally, women have an absolute fundamental right to be involved in all the decision-making around them. Not just to be involved but to lead it.

That does require some planning to be aware of the expectations. So, for example, I might be COVID-negative today. But what would happen if I come in, in labour and I am COVID-positive? What are the expectations for you and your staff? And for my partner?

What is the most important thing you want care providers to know about maternity care in a pandemic?

Oh, only one? Our research has shown that it is possible to provide woman-centred care, even in a pandemic. The midwives and doctors we spoke to talked about continuity models – where we have a relationship with a woman throughout her antenatal period – that it was protective for women and the clinician.

In the fragmented models, midwives were limited to a 15-minute face-to-face appointment, and they worried: ‘Did I miss something in the assessment? I’m never going to see this woman again.’ The anxiety burden placed on the clinician is highly significant.

So, that is the message for us as clinicians. To continue to advocate for models of care that we know is good for the women and their families and us as clinicians.

It reduces our anxiety, and it reduces our sense of burden in working within a system that is more systems-orientated to one that is more woman-centred. So if we’re looking at sustainable approaches to maternity care, in or out of pandemic times, continuity models are where the nexus of that benefit is found.

We often get fed the line in health care that ‘big ships turn slowly. They [health authorities] want to implement a continuity care model, but it takes time.

I’m sorry, but none of us will swallow that story anymore. Overnight we changed our maternity services in response to a pandemic. We have compelling data about health outcomes for women with continuity of care. We can also change our systems overnight to ensure we are centring our care on women and their needs.

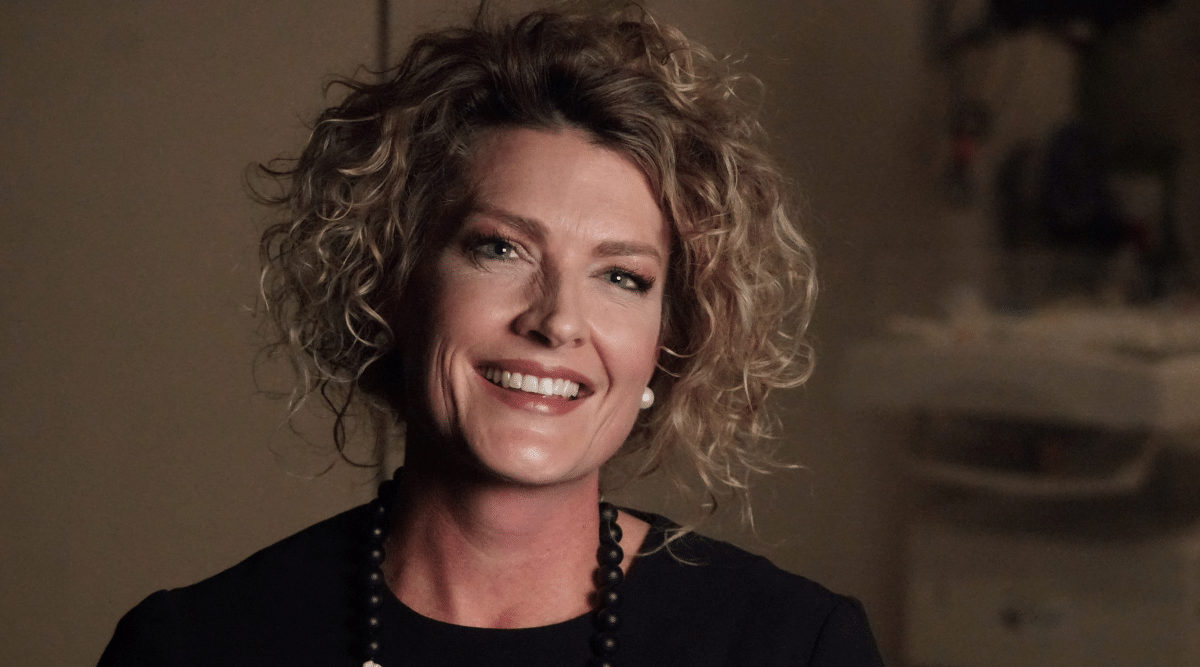

In her academic role, Dr Zoe Bradfield works at Curtin University and King Edward Memorial Hospital, Perth. Her research seeks practical outcomes that benefit women, their families and society. Zoe and her colleagues conducted surveys and interviews with women, their partners, midwives and doctors on pandemic-related changes to maternity care. As a registered nurse and midwife, Zoe is the Australian College of Midwives Vice President.

Published 17th May 2023

Recent Comments